An Ancient Tradition

Carnatic music is the system of classical music native to Southern India. Its ancient origins can be traced back over 2500 years to the oldest Hindu scriptures, known as the vedas, and since then, it has largely withstood the change that often accompanies centuries of political and religious upheaval. It shares a number of these characteristics with its counterpart from Northern India, known as Hindusthani music.

A Fine Technical Structure

Carnatic Music is one of the few musical systems of the world possessing a fine technical structure in addition to a profound aesthetic value. It is a melodic system based on fundamental sounds known as srutis, which form the basis for the definition of notes, known as svaras. Particular sets of svaras are used to construct melodies, known as ragas.

Each of the innumerable ragas of Carnatic music is defined by rules of usage of its notes including the permissible and forbidden manners of ascent and descent, the aesthetics of transitioning between notes (gamakas) and their relative prominence.

Time is measured according to beats or beat cycles known as talas.

The Many Dimensions of Compositions

Compositions in Carnatic music possess multiple dimensions:

- The aesthetic dimension refers to the melodic value profferred by the raga and its concerted usage with the lyrical dimension;

- The lyrical dimension encapsulates the meaning intended by the composer and the religious value of the lyrics, or sahitya

- The prosodical dimension describes the technical value associated with the poetic metre;

- The rhythmic dimension captures the organization of the sahitya and prosody according to the composition’s tala.

Some compositional forms in Carnatic music include the varnam, the kriti, the tillana, the javali, and the padam, some of which were derived through the intimate relationship between Indian music and Indian classical dance.

Galaxy of Composers

Over the last few centuries, Carnatic music has been endowed with thousands of compositions by a galaxy of composers, many of whom are today revered as saints. Among the most prolific are

- Purandara Dasa (1480-1564);

- Annamacarya (1408-1503);

- Tyagaraja (1759-1847);

- Muddusvami Dikshitar (1776-1827);

- Syama Shastri (1762-1827).

The last three are known as the Trinity of Carnatic Music for the profound and indelible impression that their works have had on the modern understanding of Carnatic Music.

Modes of Improvisation

Although there are many types of compositions in Carnatic Music, the music itself does not require compositions, and as a result, a very significant part of Carnatic Music is improvised. For example,

- alapana is the free exposition of a raga with the intent to convey its differentiating characteristics and aesthetic value without rhythm

- tana or madhyamakala is a mode of improvisation attempting to highlight the medium-tempo aspects of the raga through emphasis in the note transitions, resulting in a ‘perceived,’ rather than actual, rhythm;

- niraval is the extemporaneous elaboration of a particularly meaningful phrase in a composition abiding by the original placement of words therein;

- kalpanasvara is the literal rendition of the monosyllabic names associated with the basic notes, and is usually tied to the setting and tempo of a particular composition.

In order to be considered effective, each of these modes of improvisation must deliver the essential technical and aesthetic features of the raga while strictly abiding by the rules of its constitution.

The Modern Concert Format

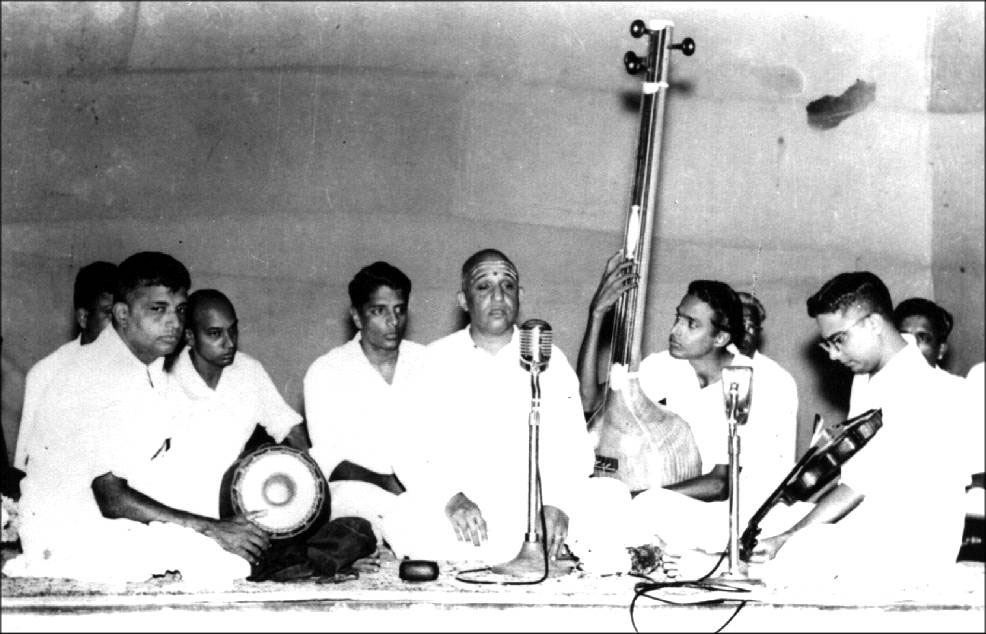

The modern Carnatic concert is often structured by the main artists, who may be vocalists or play a variety of ancient instruments including the veena (a plucked string instrument) and the bamboo flute. The main artists are typically supported by a percussion artist playing the mrdangam (a two-headed skin-based drum), who is, in turn, supported by artists playing the ghatam (clay pot), kanjira (single-sided tambourine-like instrument) and the moharsing (type of linguaphone). The violin was also introduced as an accompaniment during the British Raj and South Indian violinists have developed a unique and enviable dexterity with the instrument through its prominent role in Carnatic concerts today.

The 17th and 18th centuries saw the art form nurtured in royal courts, temples, and chamber settings, and this paved the way for the public concert format of today. Carnatic concerts consist of a number of compositions in a variety of tempos, with alapana, tana, niraval, and kalpanasvara presented for select compositions. This format is generally followed by all instrumentalists and vocalists in the Carnatic music scene today. However, some departures from the traditional format include thematic concerts focusing on particular composers, ragas, or musical forms, and lecture-demonstrations on Carnatic musical theory and practice.